The world’s largest flamenco audiovisual collection

Watch Anytime Anywhere

The Best Flamenco Music at Your Fingertips

Over 1,800 titles

Explore the largest video library of the best flamenco music

Quality and Exclusivity

Weekly and exclusive premieres produced with the highest quality

Multi-Device

Watch them on your mobile, tablet or PC

You can watch us on

TV Channel

We are in Spain on your local operator, and in France and Switzerland on Orange, SFR, Bouygues, Free, Salt.

APP

Enjoy our Webapp to Enjoy Anywhere Anytime

Prime Video

Find us on our Prime Video channel

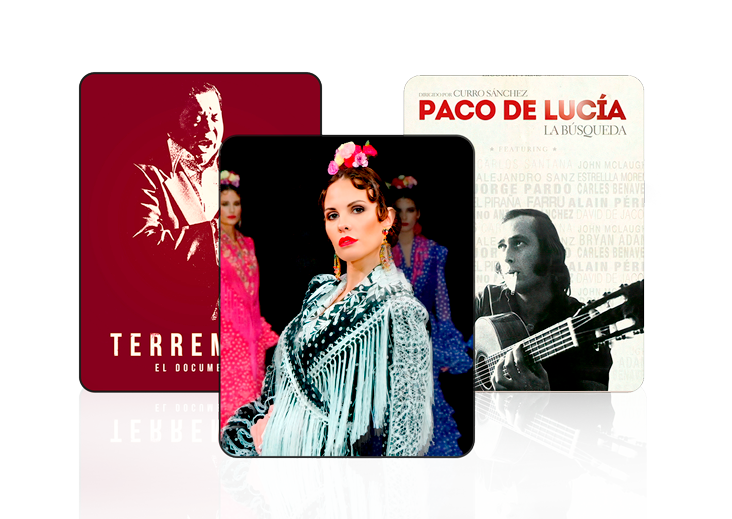

The Best Flamenco Artists in the World

Over 1,500 World-Class Artists, Past and Present

Watch an Extensive Collection of Flamenco Music

Big and small, recitals, concerts?

from theaters, peñas and emblematic places.

The Best Flamenco Dance and Singing

Pure, modern, avant-garde, classic

Documentaries, Fashion, Interviews

and so much more

Frequently Asked Questions

What is ALL FLAMENCO?

It is the streaming service and TV channel to experience the best modern flamenco music in Spanish, English and Japanese.

The most recent festivals, recitals, concerts of great artists, exclusive interviews, features, classes, flamenco fashion shows and documentaries to learn about the flamenco of yesterday, today and ever.

What is ALL FLAMENCO?

It is the streaming service and TV channel to experience the best modern flamenco music in Spanish, English and Japanese.

The most recent festivals, recitals, concerts of great artists, exclusive interviews, features, classes, flamenco fashion shows and documentaries to learn about the flamenco of yesterday, today and ever.

How to watch ALL FLAMENCO?

There are 3 ways to do it:

1) by means of our TV CHANNEL available on operators in Spain, France and Switzerland;

2) our APPs; and

3) our channel on PRIME VIDEO CHANNELS Spain. Each of these three modalities is independent and must be contracted separately.

In addition, a new APP has recently been launched through Vimeo with new functionalities that is independent from the previous one. The old APP is available exclusively for previously existing subscriptions.

How much does ALL FLAMENCO cost?

You can start discovering ALL FLAMENCO completely free by visiting our Free Content section, or subscribe to one of our plans if you want more. Check our Plans.

Is registering the same as subscribing?

No, it is independent. Registration does not imply that you have to pay anything or make any kind of commitment. First you register or sign up as a user, which will allow you to enjoy our Free Content section. You can then choose a subscription plan that will allow you to play all ALL FLAMENCO content as many times as you want.