In the flamenco universe, there are names that transcend the art. Names that become symbols, living roots of a land, a culture, and a shared memory. Camarón de La Isla is one of those names. His voice didn’t just revolutionize flamenco singing—it embodied, in every verse, the heartbeat of his hometown: San Fernando, “La Isla”, the place that forever echoed in his music, his faith, and his longing.

In this deeply evocative article, writer and flamenco enthusiast Carlos Rey invites us to rediscover Camarón through a more intimate, revealing lens: the unbreakable bond between the artist and his homeland. Through the lyrics he sang, the memories etched into his recordings, and the deep emotions tied to his upbringing, the article paints a passionate portrait of a man who made his birthplace not just a part of his name—but his banner.

This is more than just a flamenco article. It’s a journey through Camarón’s soul, his gypsy roots, his childhood by the forge, his prayers to the Nazareno, and the everyday corners of San Fernando where the legend became a neighbor, a son, a man. A must-read for flamenco lovers and for anyone seeking to understand how an artist can merge with their land until they become one and the same.

Text: Carlos Rey

Photography: Javier Fernández

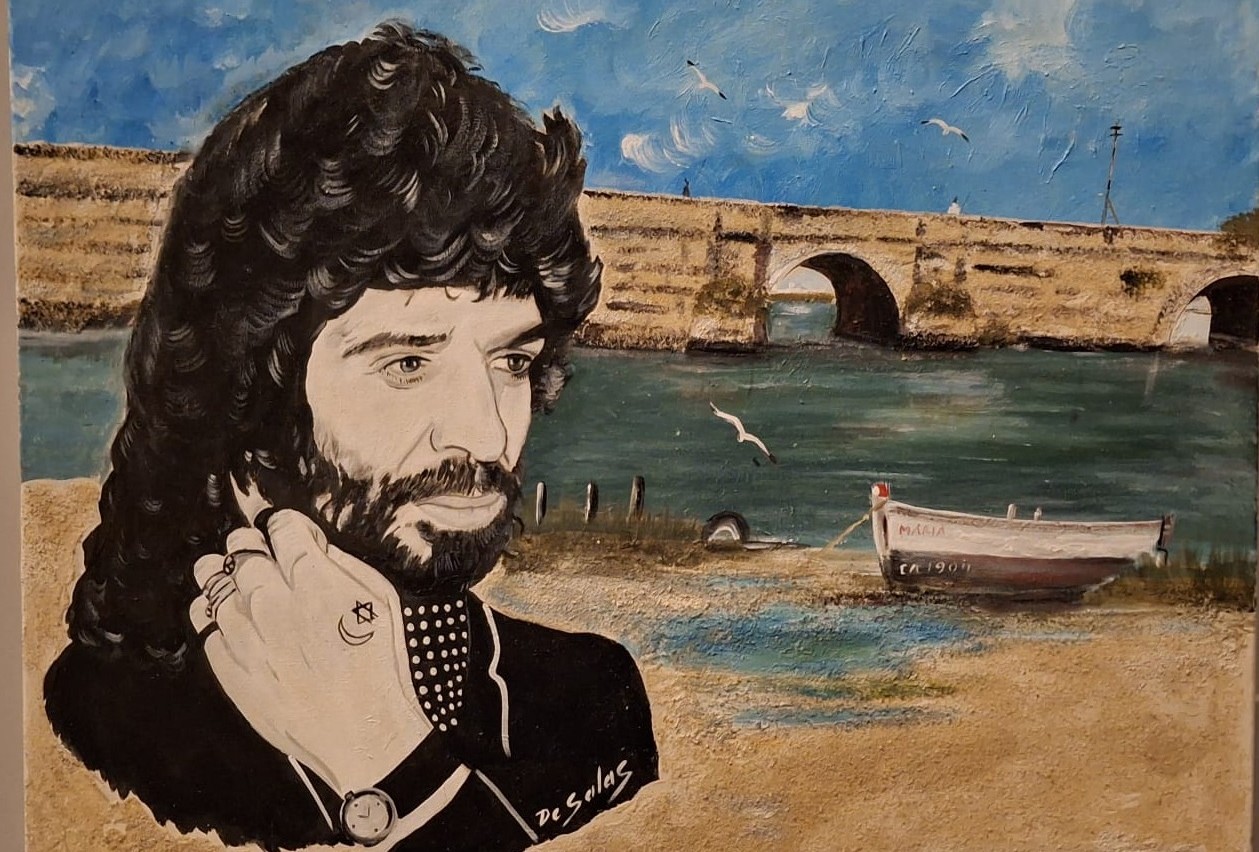

Cover artwork: Ignacio de Salas

CAMARÓN AND HIS ISLAND – By Carlos Rey

José Monje Cruz, that fair-haired gypsy boy born in the narrow streets of San Fernando, would go on to become known across the world as Camarón de La Isla. When the time came to choose a stage name, he had no doubts. He could have been Joselito el de la Juana, or Pijote as he was briefly called, or simply Camarón—as his uncle Joseíco used to call him. But he decided to be known as Camarón de La Isla, proudly honoring the land that saw his birth. He sang it this way in a 1972 cantiñas:

1.- Que a mí me vio de nacer – Cantiñas

*Que a mí me vio de nacer

Bendita sea la tierra

Que a mí me vio de nacer

Cien años que yo viviera

Siempre la recordaré.

Isla de mi corazón

Qué bonita te hizo Dios

Que donde quiera que estoy

Te tengo presente yo.

Por ti daría

La vida mía.*

To the strength with which he defended his identity, he added the deep respect and pride he felt for his lineage, his family, his roots, his people, for gypsies all over the world, for their customs and their worldview. These values were instilled in him from childhood by his parents—honest people who worked hard every day to provide for their children. In 1970, Camarón sang some fandangos by Niño Gloria that clearly expressed the pride he felt for his origins:

2.- En La Isla yo nací – Fandangos del Niño Gloria

En la Isla yo nací

Yo me crié al pie de una fragua

En la Isla yo nací

Mi mare se llama Juana

Y mi pare era Luis

Y hacía alcayatitas gitanas.

He studied at the Liceo in a time when social class determined academic access. Although he didn’t spend long there, he learned enough to navigate life. But it was in flamenco where he found his personal wellspring of wisdom—a source he drank from since early childhood, in his home and at his father’s forge. In 1986, on the album Te lo dice Camarón, he recalled his childhood this way:

3.- Otra Galaxia – Bulerías

Cuando los niños en la escuela

Estudiaban pa’l mañana

Mi niñez era la fragua

Yunque, clavo y alcayata

Yunque, clavo y alcayata.

He experienced tragedy early on, with the death of his father when he was still a child. That event profoundly marked both his life and that of his family. Camarón was a man of faith, and in the 1984 album Viviré, he told the story of a little boy who prays in church for his father’s life, even though fate sometimes has its own plans:

4.- A la Iglesia Mayor fui – Seguiriyas

*A la Iglesia Mayor fui

A pedirle al Nazareno

Que me salvara a mi pare

Me contestó que no

Que me dejaba a mi mare

Que me dejaba mi mare

A la Iglesia Mayor fui

A pedirle al Nazareno

Que me salvara a mi pare.*

That faith led him to his deep devotion to the Cristo del Nazareno. This was something he inherited directly from his mother, Juana Cruz—a woman of deep religious conviction. According to those who knew her, she was the first to arrive every morning at the main church to pray to the Nazareno. Like his mother, Camarón often sang saetas to his Christ on Holy Thursday. Just before his death, in his final album Potro de rabia y miel, he sang to him again:

5.- Mi Nazareno – Bulerías

*Mi Nazareno, mare

Es tan gitano, el de La Isla

Es tan gitano

Que los cirios que llevan

Bailan por tangos

Mi Cristo llora por dentro

Porque en la cárcel le cantan

Toíto los presos.*

Prison life and the suffering of inmates appear frequently in Camarón’s lyrics. He always included them in his prayers, as in this fandango he dedicated to his patron saint, the Virgen del Carmen, in the 1987 album Flamenco Vivo:

6.- Virgen del Carmen

Y levanta tu mano que es divina

Virgen del Carmen Sagrada

Y levanta tu mano que es divina

Y ponle tú la bendición

A aquellos que por ti suspiran

Que los condenan a muerte

Y mueren en una prisión.

José Monje was a man of his land. Not only did he love it and feel proud of it, but he also knew its landscape well and felt at ease in it. Many of his lyrics—especially those linked to cantes de Cádiz—reference the environment where he grew up. One clear example is this alegrías he sang in 1979 on his iconic album La Leyenda del Tiempo:

7.- Bahía de Cádiz – Alegrías

Esteros de Sancti Petri

Salinas de San Fernando

Espejo de sol y sal

Donde se duermen los barcos

Isla del Guadalquivir

Donde se fueron los moros

Que no se quisieron ir.

Despite being a worldly man, he never forgot his roots or his local customs. When he was in San Fernando, it was common to see him having coffee with his wife and children at La Mallorquina, or like any other local, buying a paper cone of bienmesabe fried fish at the Dean’s stand. He captured that scene in his final album Potro de rabia y miel, with lyrics by Casilda Varela:

8.- Vendo pescaíto – Bulerías

Yo vendo pescaíto a dos reales

Cómpreme un cartuchito

De bienmesabe.

José Monje Cruz, Camarón de La Isla, was—and undoubtedly remains—one of the greatest ambassadors our city has ever had. Throughout his short but intense life, he showed, both personally and artistically, the deep bond that tied him to his homeland. More than two decades after his passing, it would be only right for his city to grant this brilliant flamenco singer and proud son of San Fernando the lasting recognition he deserves.