Throughout the 20th century, Spanish cinema has been a mirror reflecting societal change, and flamenco—with its depth and charisma—has found many ways to appear on the big screen. While artists like Lola Flores or Manolo Caracol built parallel film careers alongside their artistic lives, Camarón de la Isla—symbol of modernity and duende—had a more discreet yet deeply symbolic relationship with cinema.

In this article, researcher and writer Carlos Rey traces Camarón’s few but significant appearances in film, from his teenage debut as an extra in Rovira Beleta’s El amor brujo, to his unforgettable collaboration with Carlos Saura in Sevillanas, including the film Casa Flora and the biopic directed by Jaime Chávarri. The article also explores works inspired by Camarón’s myth without featuring his physical presence, such as La leyenda del tiempo by Isaki Lacuesta.

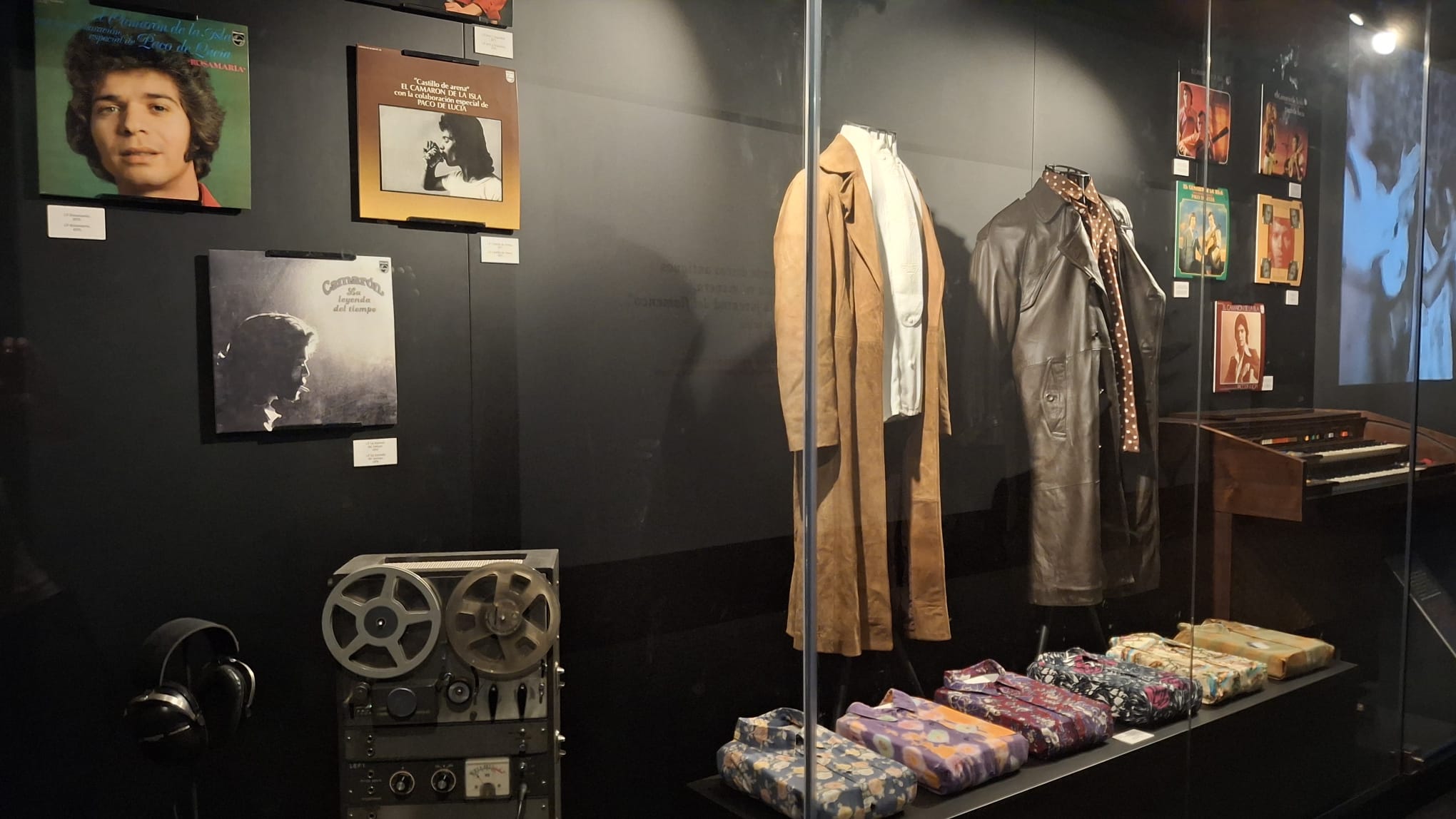

A must-read for anyone who wants to understand how Camarón’s legacy transcends music to become a visual and narrative icon of contemporary flamenco.

CAMARÓN IN FILM. By Carlos Rey. Article courtesy of Revista La Fragua.

A recurring figure in post-war Spain was the tonadillera, who, along with the bullfighter, formed an idealized couple. Copla music and bullfighting were cultural pillars, often explored by filmmakers of the era. Flamenco was also present, though often reduced to its most folkloric dimension. Notable incursions in film by flamenco legends like Manolo Caracol—who acted alongside Lola Flores in several movies, most famously interpreting Carcelero behind the bars of a cell—are well known. As early as 1927, Doña Concha Piquer debuted in cinema with El negro que tenía el alma blanca, and Lola Flores starred in Morena Clara in 1954.

That wasn’t the case for Camarón, who, despite being part of another golden era of flamenco, did not pursue a parallel career in film. He did participate occasionally, but only modestly.

The first time José Monje (Camarón) appeared in film was as an extra in Rovira Beleta’s El Amor Brujo (1967). Camarón was seventeen at the time, although some sources claim the film was shot two years earlier, which would place him at fifteen. The film, starring Antonio Gades and La Polaca, was a major production and was nominated for the Best Foreign Language Film Oscar. Part of it was shot in Cádiz and San Fernando. Due to the storyline, many Roma extras were needed, drawing people from all over the Bay. From Chiclana came El Cojo Farina and María la Paquera, among others. Alonso Núñez Heredia (Farina’s son) recalls producers playing a joke on his father—asking him to show up in Cádiz with five Roma men with mustaches and canes. The next day, Farina appeared with them, much to the amusement of the crew.

Juan Carrasco, a burly Roma man connected to the Venta Vargas circle, was also an extra. He recalls Camarón being thrilled by the filming atmosphere and eager to appear on camera. He ended up clearly visible in several scenes. Carrasco says they earned between 60 and 80 pesetas a day, and for the Roma youth of the time, it was unforgettable. Filming took place on the Cádiz pier, in Santibáñez, and in La Isla at the now-closed Venta San Lorenzo. Camarón appeared as a guitarist.

In 1973, Camarón had a small role in Casa Flora, a film by Ramón Fernández featuring stars like Estrellita Castro, Lola Flores, Arturo Fernández, and Carlos Larrañaga. This time, Camarón didn’t just appear as an extra but played a minor thief who, after robbing a jewelry store, rides a motorbike through Madrid singing El Serenito. This song by Rafael León and Juan Solano became quite popular and frequently aired on the radio. In the book La Chispa de Camarón, his widow recalls that after this scene, Camarón became famous beyond flamenco circles. Interestingly, his spoken lines were dubbed—though, of course, the song was not.

Though the film experience was enjoyable for José, he wouldn’t return to the big screen until shortly before his death. In 1992, he recorded the sevillanas Pa qué me llamas for Carlos Saura’s film Sevillanas, a refined composition by Isidro Muñoz and José Miguel Évora, directed by guitarist Manolo Sanlúcar. The finishing touch came from dancer Manuela Carrasco, Camarón’s wedding godmother.

Camarón’s cinematic journey didn’t end there. Even without his physical presence, his legend only grew, continuing to inspire film lovers.

In 2005, Isaki Lacuesta—winner of the Concha de Oro in 2011—released La leyenda del tiempo. While not strictly a film about Camarón, it is deeply infused with his spirit—not just because of the title, which references Camarón’s iconic 1979 album, but also due to the lingering aura of his image throughout the film. The plot follows two parallel stories: one of a young Roma boy from La Isla, born in 1992, who stops singing after his father is killed; and another of Maliko, a Japanese woman who travels to La Isla to see where Camarón was born and to learn to sing like him. She wants to sing, but cannot. The film stars Israel and Cheíto Gómez, two non-professional Roma brothers from the Casería neighborhood. Many locals appear in the film, including Jesús Monje “Pijote,” Camarón’s brother, who teaches Maliko cartageneras in a scene at the Camarón Peña.

I myself contributed to the film’s soundtrack with the song Playita de la Casería, which I composed in 2000 with my friend Juan A. Iglesias “Trysko.” It was sung by Pilar “La Mónica,” lead vocalist of the band EA!. The credits also feature Raimundo Amador, Montse Cortés, Carles Benavent, Joan Albert Amargós, Jorge Pardo, and Rubén Dantas performing a jam session version of La leyenda del tiempo.

In 2005, Camarón’s life was brought to the screen by director Jaime Chavarri. The film tells the story of the singer’s life from childhood until his return from the U.S., already marked by fate. While the screenplay left much to be desired, actor Óscar Jaenada delivered a masterful portrayal—capturing Camarón’s posture, singing style, and even how he held a cigarette. Much of the film was shot in La Isla. José Reyes, a Culture Department official, recalls numerous filming locations: the Camposoto beach scenes with the horse, the courtyard in Casería for a party with Manolo Caracol, the exterior of the Capuchinas Convent used as the Liceo school, and the final scenes shot inside the actual Liceo. Other scenes featured the Zuazo Bridge, the area where the old San Carlos factory crane once stood, and the street where Camarón was born—as well as the cemetery. Reyes mentions that the dawn scene with church bells was shot at 7 a.m., prompting complaints from locals.

The most recent film contribution to the Camarón legend is Tiempo de Leyenda by José Sánchez Montes, a documentary filmed in 2009 to commemorate the 30th anniversary of the album La leyenda del tiempo. It includes rehearsal footage, testimonies from project participants like Ricardo Pachón, and musicians involved in the recording—as well as figures like Juan “El Cama,” responsible for logistics. Camarón is frequently seen working with the musicians, showcasing the creative process behind what would become his most famous album. The film reveals how the songs evolved from their initial versions to the final recordings—for example, Homenaje a Federico, first sung by Kiko Veneno in skeletal form, then immortalized by Camarón in the studio.

A personality and artist like José Monje Cruz offers inspiration for much more than this. His image, life, and work will continue to inspire future generations. Camarón is not just a source—he is a spring.